- Home

- Vincent Czyz

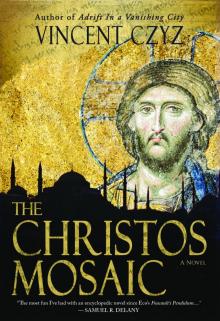

The Christos Mosaic

The Christos Mosaic Read online

Also by Vincent Czyz

Adrift in a Vanishing City

THE CHRISTOS MOSAIC

A NOVEL

VINCENT CZYZ

Blank Slate Press | Saint Louis, MO 63110

Copyright © 2015 Vincent Czyz

All rights reserved.

Blank Slate Press is an imprint of Amphorae Publishing Group, LLC

For information, contact [email protected]

Amphorae Publishing Group | 4168 Hartford Street | Saint Louis, MO 63116

Publisher’s Note: This book is a work of the imagination. Names, characters, places, organizations, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. While some of the characters, organizations, and incidents portrayed here can be found in historical accounts, they have been altered and rearranged by the author to suit the strict purposes of storytelling. The book should be read solely as a work of fiction.

www.amphoraepublishing.com

www.blankslatepress.com

www.facebook.com/vincentczyz

Cover and Interior Design by Kristina Blank Makansi

Cover Photograhy:

Hagia Sofia by Dennis Jarvis from Halifax, Canada (Turkey-3019 - Hagia Sophia

Uploaded by russavia) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Deesis Mosaic By Edal Anton Lefterov (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creative-commons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro and Felix Tilting

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015950846

ISBN: 9781943075034

I would like to dedicate this novel to my mother, Louise Jaworski. A devout Catholic, she nonetheless understands that her relationship with God is not more important than her relationship with the people in her life.

THE CHRISTOS MOSAIC

CAST OF HISTORICAL CHARACTERS

Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570–495 BC) — A mathematician and philosopher, he was also founder of a Mysteries cult and was commonly held to be the son of Apollo and a mortal virgin. According to Iamblichus, he spent twenty-two years in Egypt as a student of the Osiran Mysteries and performed any number of miracles, including calming the waves of rivers and seas in order that his disciples might the more easily pass over them.

King Jannai, Alexander Jannaeus — a Hasmonean king who ruled Judea from about 104 to 78 BC. The Pharisees, furious that the Hasmoneans had usurped the office of high priest, rebelled against him in 94 BC. After six years of civil war, Jannai won decisively and exacted revenge by crucifying eight hundred Pharisees. Part of their torture was to watch soldiers slash the throats of their wives and children.

Jesus Panthera, Yeshu Pandera or Pantera — Put to death during the reign of King Jannai, Yeshu ben Panthera was allegedly the best student of Yehoshua ben Perachiah, with whom he had fled to Egypt to escape Jannai’s persecution of the Pharisees. He is mentioned only in the Talmud, and there is great confusion and disagreement as to exactly which passages refer to him and what is actually said about him. It is generally believed that he learned magic in Egypt, became a religious teacher, and attracted five disciples. He was stoned to death as a sorcerer on the eve of Passover.

Judas of Galilee, Judas the Galilean — In 4 BC, after the death of Herod the Great, a Zealot named Judas attacked Sepphoris, a wealthy, cosmopolitan city in Galilee. He and his followers broke into the armory and began a revolt against the Roman-backed rule of Herod’s descendants. Some scholars (with whom I agree) believe this was the first time Judas of Galilee rebelled against Roman rule. His better-known regional uprising against Roman rule took place in 6 AD. He also founded Josephus’s fourth sect, the Zealots, as well as the Sicarii—Zealots who functioned as assassins. They are named after the small daggers, or sicae, they kept concealed under their clothing. Judas, mentioned in Acts 5:37, is thought to have died at Roman hands although Josephus never says how he was killed.

Philo of Alexandria, Philo Judaeus (25BC – 50 AD) — A Hellenized Jew who interpreted Jewish scripture allegorically and attempted to harmonize Greek philosophy with Jewish philosophy. He believed that a literal reading of the Old Testament would severely limit humanity’s understanding of God. His concept of the Logos as the personification of God’s wisdom had a clear influence on Christian thought. He also believed that Moses (as well as the prophet Jeremiah) was a hierophant (a high priest of the Mysteries) and that Judaism was a Mystery religion. A prolific writer, he was a well-known commentator on Judaism and other religions.

Seneca (4 BC – AD 65) — An exact contemporary of Jesus, he was a Roman statesman, Stoic philosopher, and tragedian. He was also advisor to the emperor Nero. His elder brother, Gallio, is mentioned in Acts.

Josephus (38–107 AD) — Born Joseph ben Matityahu, Josephus authored Antiquities of the Jews and The Jewish War, two books that remain scholars’ greatest source of information about 1st century Palestine. Originally a Zealot who fought the Romans, he later embraced the Roman general (Flavius) Vespasian as the Messiah and is now known by his Roman name, (Flavius) Josephus.

Simon Bar Giora — Although he was of peasant stock, Simon’s skill with a sword and natural gift for leadership eventually brought an army of 40,000 under his command. According to Josephus, Simon entered Jerusalem in 69 AD as a savior and a preserver. He reigned as king, had coins struck with the motto Redemption of Zion, and was thought by many to be the Messiah. When Jerusalem fell to the Romans, however, he was captured, sent to Rome, publicly tortured, and executed.

Ananus — A Sadducee, he held the office of high priest for only three months, but in that time committed his most memorable act and brought James the Just before the Sanhedrin; James was subsequently stoned to death. In 68 AD, during the First Jewish Uprising against Rome, Ananus sided with the Romans and was killed by Edomites, with whom the Zealots had allied themselves.

Ebionites — Their name is derived from the Hebrew word ebyonim or ebionim, meaning “the poor” or “the poor ones.” They were early Christians who observed Jewish law. Although they considered Jesus to be the Messiah, they did not believe he was the son of God. Of the four Gospels, they considered only Matthew to be valid. They revered James the Just, and rejected Paul as an apostate in violation of the Law. According to Gibbon, “Although some traces of that obsolete sect may be discovered as late as the fourth century, they insensibly melted away either into the church or the synagogue.”

Papias (c. 70–140) — Bishop of Hieropolis in Asia Minor (Pamukkale in modern-day Turkey), Papias claimed that Matthew’s Gospel was originally written in “Hebraic dialect” (probably Aramaic). Very little is known about him although he is said to have compiled Expositions of the Sayings of the Lord in five books, all of which have been lost. Only fragments survive.

Saint Justin Martyr (100–165) — A Christian apologist born of pagan parents, he considered himself a Platonist until a conversation with an elderly man convinced him to convert. He eventually founded a school in Rome, where he was denounced as a Christian and, after refusing to sacrifice to the gods, beheaded according to Roman law. Most of his writings are now lost, but two apologies and his most famous work, Dialogue With Trypho, have survived.

Saint Hegesippus (c. 110–180) — A Christian convert from Judaism, he was a historian of the Church who wrote prolifically. His entire body of work, however, has been lost with the exception of eight passages recounting Church history as quoted by Eusebius.

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215) — Born in Athens to pagan parents, he converted to Christianity and, after travelling the world, settled in Alexandria, Egypt, where in 190 he became head of the Ca

techetical School of Alexandria.

Saint Origen (184–254 AD) — Born in Alexandria, Egypt, he became a pupil of Clement of Alexandria. He later founded a school in Caesarea and in his numerous commentaries on the Bible advocated for symbolic and allegorical readings of scripture rather than literal readings.

Eusebius of Caesarea (260 – 340 AD) — Often referred to as the Father of Church History, he studied in the school established by Origen in Caesarea and in 314 became bishop of Caesarea. While his most important book is The History of the Church, Eusebius is known to have been a fanatical defender of Christianity and is often unreliable.

Muhammad the Wolf (Muhammad adh-Dhib) – Bedouin shepherd who accidentally discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls in caves along the shore of the Dead Sea in 1947.

John Allegro – Born in London, England in 1923, John Allegro was the only scholar on Father de Vaux’s international team who was not a Catholic. He was often at odds with other team members studying the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Father Roland de Vaux - Director of the Ecole Biblique et Archeologique, a Dominican school based in Jerusalem. Deeply conservative, both religiously and politically as well as reputedly anti-Semitic, he grew up in France and ultimately led the international team that studied a trove of Dead Sea Scrolls and scroll fragments found in Cave 4 in 1952.

HISTORICAL TIMELINE

BC

198

Judea comes under the control of the Seleucids, the Greek dynasty established in Syria after the death of Alexander the Great.

167-164

Judas the Maccabee (Judas the Hammer) leads a successful revolt against the Seleucid King, Antiochus IV. The Temple is rededicated (an event commemorated by Hanukkah) and the Hasmonean Dynasty is established.

Late 2nd Century

The Essene community at Khirbet Qumran is established as a protest against the Hasmoneans, who took over the office of High Priest, which the Essenes demanded go to a Zadokite, that is, a descendent of Zadok, grandson of Aaron and grandnephew of Moses. Zadok served as the first High Priest in the First Temple built by Solomon.

67-63

Civil war breaks out with two Hasmonean brothers vying for power. King Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, the High Priest, lead the opposing sides. Each brother appeals to foreign powers, such as the Greeks and Parthians, to intervene on his behalf. Both eventually turn to the Roman general Pompey, who has just conquered Seleucid Syria, and while he ends the war and settles the dispute, Jewish independence is gradually lost to Rome.

40

The Roman senate proclaims Herod king of Judea, effectively ending the Hasmonean struggle to regain power.

6

Extrapolating from Matthew, Jesus of Nazareth is born about two years before the death of Herod in 4 BC.

4

King Herod dies and Judas of Galilee initiates a local revolt.

AD

6

Judea is placed under a Roman prefect and, at the order of Rome, Quirinius conducts a census for tax purposes, which Luke later mentions as coinciding with the birth of Jesus of Nazareth. Judas of Galilee re-emerges and leads a revolt to protest the new Roman taxes.

26-36

Pontius Pilate rules Judea as prefect.

30

Most scholars think the Crucifixion took place in 30 AD.

48-60

The Apostle Paul composes his letters.

66-74

The Jews rise up as a nation and revolt against Rome.

68

The Essene community at Qumran is destroyed, and the Essenes are likely annihilated in the battles against Rome.

70

The Romans capture Jerusalem, and the Roman general Titus orders the destruction of the Second Temple.

75-85

The Gospel of Mark is composed by an unknown author and circulates unsigned.

85-95

The Gospel of Matthew is composed by an unknown author and circulates unsigned.

90-110

The Gospel of Luke and Acts of the Apostles are composed by the same unknown author and circulate unsigned.

95-120

The Gospel of John is composed by an unknown author and circulates unsigned.

Our age is retrospective. It builds the sepulchres of the fathers. It writes biographies, histories, and criticism. The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? […W]hy should we grope among the dry bones of the past, or put the living generation into masquerade out of its faded wardrobe? The sun shines to-day also. There is more wool and flax in the fields. There are new lands, new men, new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature

BOOK 1: 1 - 2

CONFEDERATES OF THE DEVIL

Though he was mortal, yet he was of great antiquity, and most fully gifted with every kind of knowledge, so that the mastery of a great many subjects and arts acquired for him the name Trismegistus [Thrice-Great]. He authored books and these in large number, relating to the nature of divine things, in which he avows the majesty of the supreme and only God and mentions Him by those titles which we Christians use—God and the Father.

— Lactantius, Institutes

1: 1

TWO WISE MEN

SAINTS LIE. At least as far as Drew was concerned, Saint Augustine had. The question was whether or not his paper presented a convincing argument. Uncharacteristically early for class, he was sitting at one of those minimalist desks that looked more like a chair with a paddle for an arm. His hands were probably as cold as the steel tubing the plywood seat was screwed into. It was the same chill that deadened them before a wrestling match. Today they were getting back their term papers—a hefty fifty percent of their final grades.

December light streamed through a row of tall windows. Drew could see the slate walks of the mall and the wilted lawns flecked with dead leaves. Laaksonen Hall was a nineteenth century brownstone renovated to accommodate classrooms, and from out there, he knew, the windows looked like bronze panels in the late-afternoon sun.

It probably hadn’t been a good idea taking on a saint, especially the author of City of God, an epic tome written to explain why pagan Rome had stood for nearly a thousand years, but shortly after making Christianity its official religion, had been sacked by the Visigoths, presaging the disintegration of the empire. And then there was Augustine’s Confessions, a sort of eternally bestselling memoir recounting the saint’s spiritual conflicts. Professor de la Croix, as it happened, was particularly fond of Augustine, once remarking that he’d had more influence on Christianity than any writer since the apostle Paul.

Drew used to picture the saint, robed in black, habitually sequestering himself in a stone tower overlooking a shore of North Africa. There, as Drew imagined it, he peered down a corridor of time as if through a telescope, in search of the moment when God’s infinite design had first been set in motion. Or, quill in hand, scratched out his meditations by oil lamp in such profound early-morning stillness he could hear the continents drift.

Drew’s research, however, had revealed a very different Augustine, a cantankerous old man more interested in spin than truth. One chapter of Confessions was titled: “Whatever has been correctly said by the heathen is to be appropriated by Christians.” In other words, if philosophers— particularly the Platonists—had said anything that agreed with Christianity, Augustine insisted it was up to Christians to claim it as their own since the pagans had “unlawful possession of it.”

While church officials presided over book burnings, enthusiastically consigning to flames works now considered classics of antiquity, Augustine wrote a polemic declaring that “good men undertake wars,” particularly when it is necessary “to punish” or to enforce “obedience to God.” So much for

Christ’s call for love and compassion.

Drew’s head turned when the door opened, but it was Jesse Fenton. Her skin pale, and her dark hair brutally short, she had a disarming smile and a sky-high IQ. At the fetish level, what Drew found irresistible was an abundance of freckles—forehead to chin and even the top of her chest. She nodded to him without quite smiling. They never saw each other outside of class, but there was a tacit understanding between them that they were the two best students.

Drew glanced down at his notes. As disappointed as he was in Augustine, he wasn’t interested in exposing his faults. An English major with a minor in religion, he’d been caffeinated to the point of insomnia by the idea of welding the two disciplines together. While tracing the influence of the occult in Romantic poetry, he’d come across Augustine’s critique of the Corpus Hermeticum, which, by the Middle Ages, had become a compendium for alchemists. There, in Augustine’s argument, was a fabricated accusation; to put it bluntly, he’d lied.

Drew couldn’t use Augustine’s critique for his English course, but he’d found a place for it in de la Croix’s New Testament class. He knew he’d written an A paper—he had a 4.0 within his major—but he was hoping for something extra, some kind of acknowledgment from Professor de la Croix that he’d done first-rate work.

The problem was she couldn’t stand him. She made snide remarks when he walked in late. She called on him when she thought he wasn’t paying attention, and was delighted when she was right. While he got good grades, there was always a grudging comment on his test or at the end of a paper.

The Christos Mosaic

The Christos Mosaic